1913年 , 维也纳如何改变了世界

一战前名符其实的帝都,也是无数天才人物集聚的场所。相比之下,巴黎、伦敦、纽约之流都弱爆了。数数看历史中必然留名的,希特勒、托洛茨基、铁托、弗洛伊德、斯大林……此外,克林姆特当然早已功成名就,而穆齐尔在维也纳技术大学管理图书,勋伯格在音乐学院教和声;还有维也纳大学里的师生们:米塞斯当时还是一名编外讲师,薛定谔刚在第二物理研究所崭露头角,维特根斯坦成了帝国数一数二的富豪,莫雷诺开始最早的心理剧实验,阿德勒与弗洛伊德趋向决裂,而哈耶克与波普尔则是文法学校内的小屁孩。

1913年的维也纳如何改变了世界

BBC 2013年4月20日

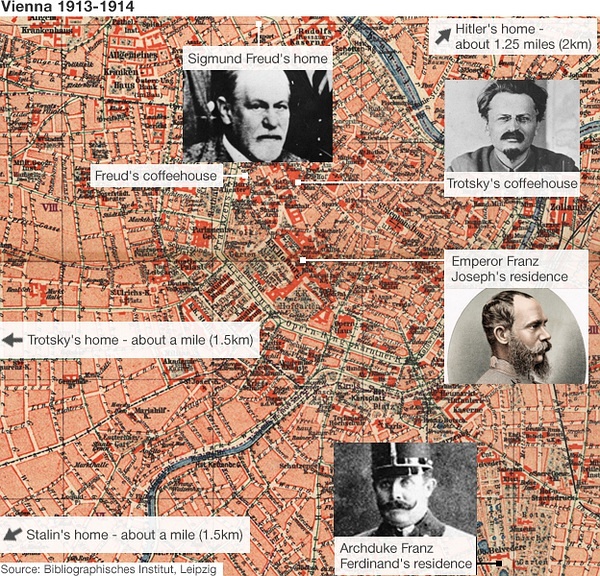

一个世纪之前,希特勒、托洛茨基、铁托、弗洛伊德和斯大林曾经同时在奥地利首都维也纳活动。

《真理报》的一名异见编辑、左翼领袖托洛茨基曾经写道,他于1913年1月与持假护照的斯大林在维也纳会面。

斯大林和托洛茨基是1913年生活在维也纳中心的两位重要人物之一,这些人命中注定塑造了(或者说粉碎了)20世纪大部分的世界历史。

这些重要人物当时的境遇各有不同。斯大林和托洛茨基是在逃的革命家,而弗洛伊德已经非常有名。

知名精神分析学家弗洛伊德当时已经在维也纳执业。

当时尚年轻的前南斯拉夫领导人铁托在维也纳以南维也纳新城的戴姆勒车厂工作,寻求就业、金钱和美好的时光。

与此同时,希特勒正在维也纳美术学院学习。当年24岁的希特勒来自奥地利西北部,为追求自己的艺术梦想居住在多瑙河附近Meldermannstrasse的廉价旅馆里。

1913年的维也纳是奥匈帝国首都。这个帝国下辖15个国家,人口超过5000万人。

1848年革命后继位的奥匈帝国皇帝弗兰茨·约瑟夫居住在霍夫堡皇宫。

皇储斐迪南大公居住在附近的美景宫,热切等待继承皇位。斐迪南大公1914年被暗杀,引发第一次世界大战。

奥地利唯一英文月刊《维也纳评论》主编麦克纳米在维也纳居住了17年。她说,1913年的维也纳虽然不能说是一个“大熔炉”,但确实是自身特有的一种文化“浓汤”,吸引奥匈帝国各地的有野心人士。

麦克纳米介绍:“当时维也纳200万人口中,不到一半在本地出生,约1/4来自现属捷克的波希米亚和摩拉维亚地区,所以很多维也纳居民除了讲德语也讲捷克语”。

“奥匈帝国的居民讲数十种语言,军队官员除了德语之外,需要用其它11种语言下达命令,每一种语言都有国歌的官方翻译”,她说。

这种混杂的局势创造了一种独特的文化现象——维也纳咖啡馆。维也纳咖啡馆的起源相传是1683年奥斯曼土耳其军队攻城失败后留下的装满咖啡豆的麻袋。

《1913:寻找大战前的世界》一书作者、英国皇家国际关系研究所高级研究员查尔斯·埃默森说:“咖啡文化和在咖啡馆举行辩论的概念是当年和今天的维也纳文化”。

埃默森解释:“维也纳的知识界其实很小,大家彼此都认识,这为跨文化的交流提供了条件,也对政治异见人士和在逃人士有利”。

他还说:“对在逃的异见人士来说,维也纳是欧洲最好的藏身之处,因为可以结识很多有意思的人”。

弗洛伊德最喜欢的Landtmann咖啡馆仍然伫立在维也纳内城区。

托洛茨基和希特勒经常光顾的Central咖啡馆只有几分钟的步行距离,那里的蛋糕、报纸、象棋,当然最重要的是那里发生的讨论点燃食客们的激情。

《维也纳评论》主编麦克纳米说,让这些咖啡馆变得重要的部分原因是,大家都去,所以各方兴趣汇集起来,西方思维中的严格界限在这里变得很灵活。

她表示,除此之外,犹太人知识界、新工业阶层在1867年获得奥匈帝国皇帝弗兰茨·约瑟夫授予完整公民权、可以上大学之后,1913年逐步崛起。

尽管维也纳当时、现在仍然是音乐、豪华舞会、华尔兹的代名词,它也有黑暗惨淡的一面——当时很多维也纳居民生活在贫民窟,1913年有近1500人自杀。

尽管没有人知晓,希特勒当年是否曾经偶遇托洛茨基、铁托或者斯大林,但是劳伦斯·马克斯2007年创作的广播剧《弗洛伊德现在可以见你,希特勒》等作品想象了这种场景。

第二年(1914年)点燃的战争之火摧毁了维也纳的知识界。

奥匈帝国于1918年分崩离析,推动了希特勒、斯大林、托洛茨基和铁托开始永远改变世界的历史。

1913: When Hitler, Trotsky, Tito, Freud and Stalin all lived in the same place

By Andy Walker Today programme, BBC Radio 4

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21859771

A century ago, one section of Vienna played host to Adolf Hitler, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Tito, Sigmund Freud and Joseph Stalin.

In January 1913, a man whose passport bore the name Stavros Papadopoulos disembarked from the Krakow train at Vienna's North Terminal station.

Of dark complexion, he sported a large peasant's moustache and carried a very basic wooden suitcase.

"I was sitting at the table," wrote the man he had come to meet, years later, "when the door opened with a knock and an unknown man entered.

"He was short... thin... his greyish-brown skin covered in pockmarks... I saw nothing in his eyes that resembled friendliness."

The writer of these lines was a dissident Russian intellectual, the editor of a radical newspaper called Pravda (Truth). His name was Leon Trotsky.

The man he described was not, in fact, Papadopoulos.

He had been born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, was known to his friends as Koba and is now remembered as Joseph Stalin.

Trotsky and Stalin were just two of a number of men who lived in central Vienna in 1913 and whose lives were destined to mould, indeed to shatter, much of the 20th century.

It was a disparate group. The two revolutionaries, Stalin and Trotsky, were on the run. Sigmund Freud was already well established.

The psychoanalyst, exalted by followers as the man who opened up the secrets of the mind, lived and practised on the city's Berggasse.

The young Josip Broz, later to find fame as Yugoslavia's leader Marshal Tito, worked at the Daimler automobile factory in Wiener Neustadt, a town south of Vienna, and sought employment, money and good times.

Then there was the 24-year-old from the north-west of Austria whose dreams of studying painting at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts had been twice dashed and who now lodged in a doss-house in Meldermannstrasse near the Danube, one Adolf Hitler.

In his majestic evocation of the city at the time, Thunder at Twilight, Frederic Morton imagines Hitler haranguing his fellow lodgers "on morality, racial purity, the German mission and Slav treachery, on Jews, Jesuits, and Freemasons".

"His forelock would toss, his [paint]-stained hands shred the air, his voice rise to an operatic pitch. Then, just as suddenly as he had started, he would stop. He would gather his things together with an imperious clatter, [and] stalk off to his cubicle."

Presiding over all, in the city's rambling Hofburg Palace was the aged Emperor Franz Joseph, who had reigned since the great year of revolutions, 1848.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, his designated successor, resided at the nearby Belvedere Palace, eagerly awaiting the throne. His assassination the following year would spark World War I.

Vienna in 1913 was the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which consisted of 15 nations and well over 50 million inhabitants.

"While not exactly a melting pot, Vienna was its own kind of cultural soup, attracting the ambitious from across the empire," says Dardis McNamee, editor-in-chief of the Vienna Review, Austria's only English-language monthly, who has lived in the city for 17 years.

"Less than half of the city's two million residents were native born and about a quarter came from Bohemia (now the western Czech Republic) and Moravia (now the eastern Czech Republic), so that Czech was spoken alongside German in many settings."

The empire's subjects spoke a dozen languages, she explains.

"Officers in the Austro-Hungarian Army had to be able to give commands in 11 languages besides German, each of which had an official translation of the National Hymn."

And this unique melange created its own cultural phenomenon, the Viennese coffee-house. Legend has its genesis in sacks of coffee left by the Ottoman army following the failed Turkish siege of 1683.

"Cafe culture and the notion of debate and discussion in cafes is very much part of Viennese life now and was then," explains Charles Emmerson, author of 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War and a senior research fellow at the foreign policy think-tank Chatham House.

"The Viennese intellectual community was actually quite small and everyone knew each other and... that provided for exchanges across cultural frontiers."

This, he adds, would favour political dissidents and those on the run.

"You didn't have a tremendously powerful central state. It was perhaps a little bit sloppy. If you wanted to find a place to hide out in Europe where you could meet lots of other interesting people then Vienna would be a good place to do it."

Freud's favourite haunt, the Cafe Landtmann, still stands on the Ring, the renowned boulevard which surrounds the city's historic Innere Stadt.

Trotsky and Hitler frequented Cafe Central, just a few minutes' stroll away, where cakes, newspapers, chess and, above all, talk, were the patrons' passions.

"Part of what made the cafes so important was that 'everyone' went," says MacNamee. "So there was a cross-fertilisation across disciplines and interests, in fact boundaries that later became so rigid in western thought were very fluid."

Cafe Central, Vienna Both Trotsky and Hitler sipped coffee under Cafe Central's magnificent arches

Beyond that, she adds, "was the surge of energy from the Jewish intelligentsia, and new industrialist class, made possible following their being granted full citizenship rights by Franz Joseph in 1867, and full access to schools and universities."

And, though this was still a largely male-dominated society, a number of women also made an impact.

Alma Mahler, whose composer husband had died in 1911, was also a composer and became the muse and lover of the artist Oskar Kokoschka and the architect Walter Gropius.

Though the city was, and remains, synonymous with music, lavish balls and the waltz, its dark side was especially bleak. Vast numbers of its citizens lived in slums and 1913 saw nearly 1,500 Viennese take their own lives.

No-one knows if Hitler bumped into Trotsky, or Tito met Stalin. But works like Dr Freud Will See You Now, Mr Hitler - a 2007 radio play by Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran - are lively imaginings of such encounters.

The conflagration which erupted the following year destroyed much of Vienna's intellectual life.

The empire imploded in 1918, while propelling Hitler, Stalin, Trotsky and Tito into careers that would mark world history forever.

You can hear more about Vienna's role in shaping the 20th Century on BBC Radio 4's Today programme on 18 April.